It’s nearly Belmont Stakes time: the late spring sun glints off the rail, the grandstand buzzes with nervous energy, and online the glow of my phone chimed as a “young” follower messaged me: Will we ever see another Triple Crown winner? He reminded me that it’s been almost a decade since Justify swept the three jewels, which—for someone barely into his twenties—feels like a lifetime. I laughed, leaned back, and began to type this reflection.

Justify’s triumph in 2018 came on the heels of American Pharoah’s in 2015—a stunning pair of champions after a 37-year drought since Affirmed’s 1978 victory. I recall my astonishment when friends asked if I expected two winners in three years, especially after so many voices had lamented that the Triple Crown was simply too grueling to ever conquer again. Three years earlier, pundits clamored to “fix” the Crown; now everyone stood in awe of its very possibility.

What never ceases to fascinate me is how wildly expectations can differ from reality. Every morning the media spews breathless commentary on the latest “data point,” as if each headline were a lightning bolt demanding immediate action. Having spent intimate hours with true “variation” experts—small, intense gatherings around dry-erase boards scrawled with bell curves and control limits—I learned to see beyond that static. Without those late-night debates, I’d have dismissed statistical theory as academic mumbo-jumbo. But the chance to probe, to question until I grasped the fundamentals, unlocked for me a realm of predictability, leadership insight, and psychological savvy that, frankly, few ever discover.

So what is variation, and why does it matter? Simply put, it’s our tool for judging how likely events are—and whether the ones we observe are ordinary or extraordinary. Imagine knowing your chances before betting on a horse, trading stock options, buying a used car, or feasting on McDonald’s cheeseburgers every night for five years. Such probabilities don’t just guard your wallet—they can determine your stress levels, your health, even your lifespan.

Beyond that, discerning normal from abnormal events saves us from frantic, wasted efforts. I’ve witnessed managers pounding conference tables, screaming at employees, concocting flashy slogans—every reaction born of a data point that, under a stable system, was utterly predictable. Meanwhile, a truly enlightened leader ignores those expected fluctuations and instead rallies her team to reengineer the flawed process itself.

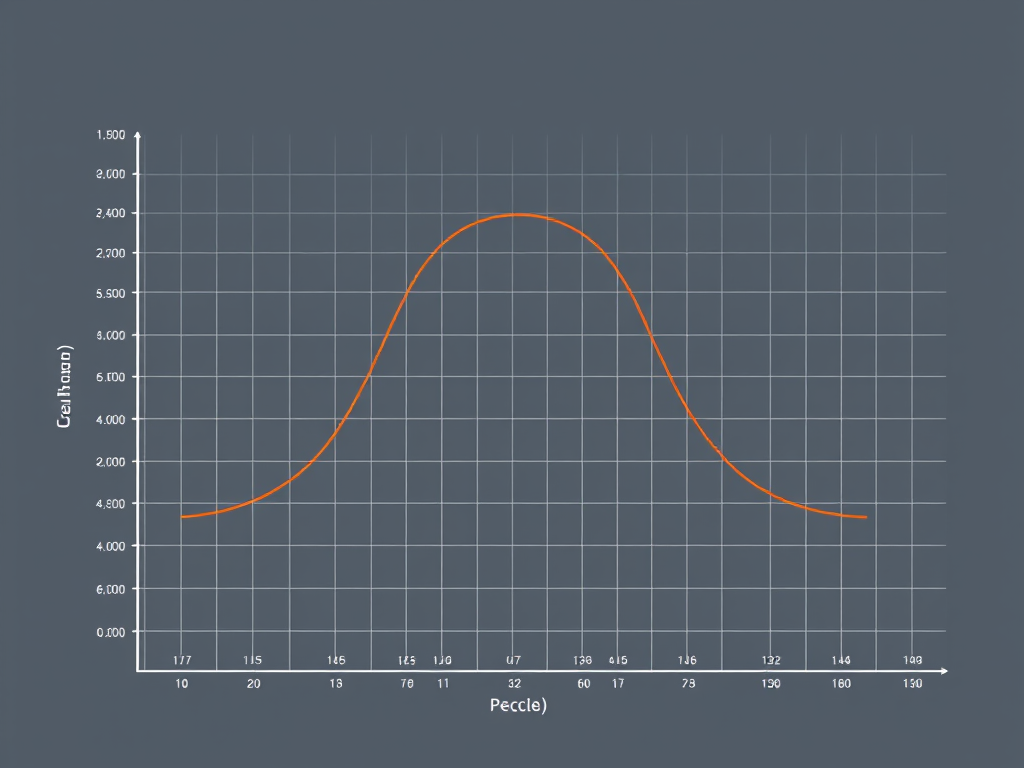

Most people have seen the bell-shaped curve, but how many truly grasp it? Picture a gentle hill stretching to the horizon: that’s your distribution of outcomes. Everything—every newspaper headline, every TV commercial, every sporting upset, every blackjack hand, every choice you make—follows some version of that shape. Those who ignore variation chase phantom causes; those who understand it see the system clearly.

We learn of “cause and effect” in school, yet the same institutions often neglect to teach variation. As a result, generations react to effects without ever probing true causes. In statistical parlance, there are two kinds of causes:

• Common causes—built into the system itself. When data points lie within calculated “control limits,” the system is stable, and those outcomes are simply its natural hum. Horse racing, with records stretching back to the 1890s, is such a system: its mechanics haven’t changed dramatically, even as the number of foals born each year has dwindled. From historical times you can compute its limits and identify which race results fall into routine variation.

• Special causes—unusual events that lie outside those limits, true departures from the norm.

Mistakes happen whenever you treat common-cause noise as if it were special-cause signal—and vice versa. Yet the modern world trains us to fixate on each new data point. The media crafts sensational narratives around them; advertisers exploit our urge to react; and so we’ve learned that the slightest blip demands action.

Now imagine a sea of ninety-eight people, each riding an emotional rollercoaster at every beep of new information: they dissect it, debate it, manage by it, invest in it. Meanwhile you stand apart with your mastery of variation, predicting not just single outcomes but entire ranges of plausible results. Whether at the pari-mutuel window, the stock exchange, or the supermarket checkout, you hold a decisive edge over those dazzled by recent headlines.

Still, many confuse special causes for system flaws, and accuse stable processes of being “random.” This confusion is not always ignorance—it’s often an emotional shield to justify past decisions. Consider the motorcyclist who forgoes a helmet because an uncle rode helmetless for decades without injury. Or the lifelong smoker who insists he’s immune because “nothing’s happened so far.” Or the high-protein zealot who points to a vegetarian friend who succumbed to cancer at thirty. Or the patient endlessly medicated for symptoms while the root disease goes unaddressed. After my years in healthcare, these life-and-death choices strike close to home. Denial of systemic truths leads to tragedies, followed by elaborate attempts to patch the damage.

Let’s return, then, to the Triple Crown. Since 1919, thirteen horses have achieved the sweep—a rate of about 13 percent. Framed properly, that’s roughly the same odds as rolling a six or an eight with two dice, or drawing two blackjacks at a six-hand blackjack table in eleven deals. It’s common-cause variation—utterly ordinary, no matter how thrilled or surprised we feel when it happens twice in four years.

So here it is: my long-winded answer to a simple question. Will we see another Triple Crown winner? Statistically, you’re as likely to witness one as you are to roll that six or eight on any given throw. And with your newfound grasp of variation, you’ll no longer mistake chance for miracle. As Yoda wisely told us, “There is no try. There is only do or do not.” God gave us brains, eyes, and ears to uncover truth—even statistical truth—and to let science guide our decisions.

Yes, this was the longest reply you could imagine. C’est la vie.

Leave a comment